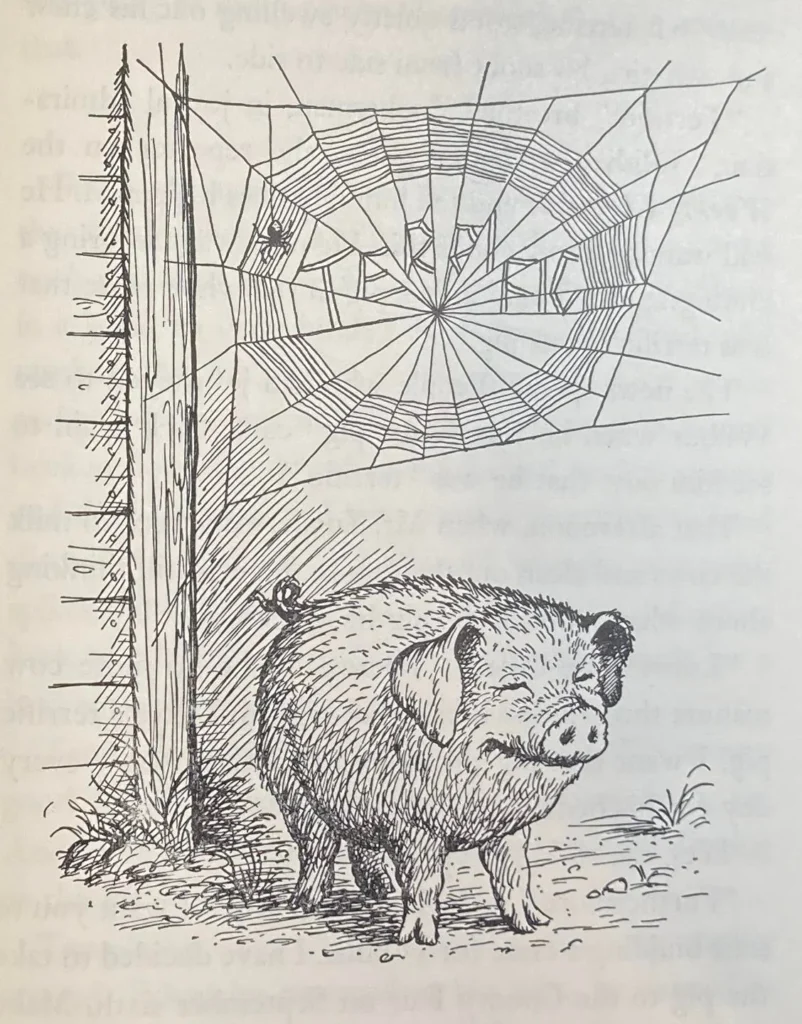

I’ve always loved talking animals in books and films. My all-time favourite talking animals are Wilbur the Pig, Templeton the Rat and Charlotte the Spider from Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White. I remember watching the film on ‘movie day’ in elementary school. Tears ran down my face when Charlotte died. Little did I know then, this story introduced me to the concept of death. Looking back now, it also taught me about life.

Who are your favourite talking animals? Winnie-the-Pooh? The Velveteen Rabbit? Scoobie-Doo?

The Chronicles of Narnia author, C. S. Lewis, whose fantastical stories contain talking horses and mice, once noted that “a single second of lived time contains more than can be recorded.”

Anthropomorphic animals (giving a human voice, costumes, and other human qualities to animals) are enchanting, entertaining and just plain cute – but they also have influenced history and storytelling in profound ways.

There’s something about learning about life – adventures lived and lessons learned – that comes from listening to real, live creatures talk (fictional or not). Guess what? We are creatures too.

For most of the past, people didn’t read or write. They shared their stories – their history – by orally recounting their experiences. It wasn’t only indigenous societies who did this. The very origins of Western-based history lie in ancient Greece where the first known historians like Thucydides and Herodotus first began by interviewing living witnesses to key events.

However, over time, at least in Western society, oral history became considered the poor cousin to written official records.

But here’s the problem with written sources. They leave gaps. The author (or historian) may skim over the complete context in favor of eloquent prose. What our voices and expressions can capture, with vivid and remarkable candor, are the connective thews, vocal timbre, reactions (including meaningful pauses), and lived experiences. That is what oral history offers us.

The authentic record of history is found in the lives of the ordinary people who lived it. Collecting, preserving and sharing oral histories not only transmits knowledge from one generation to the next, it enhances our understanding of the past by illuminating personal experience.

Oral history may not be the best method for obtaining factual data because people rarely remember such detail accurately. However, oral history is useful (and enchanting, and entertaining) to get an idea not only of what happened, but what past times meant to people and how it felt to be a part of those times.

We need history for identity. It is human nature to use stories to explain things.

Over this past year developing Sincerely Yours I have never been so thankful and fascinated to help capture your stories or the stories of your loved ones. I am tremendously grateful for the trust of so many remarkable families and I hope (and highly suspect) your stories will leave an indelible mark on those around you – now and in the future.

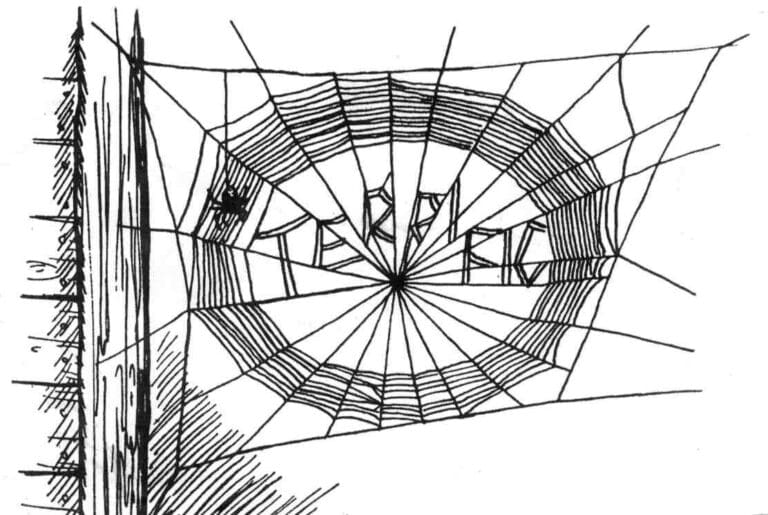

From Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White:

“Why did you do all this for me?’ Wilbur asked. ‘I don’t deserve it. I’ve never done anything for you.’

“You have been my friend”, said Charlotte, “That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you. After all, what’s a life, anyway? We’re born, we live a little while, we die. A spider’s life can’t help being something of a mess, with all this trapping and eating flies. By helping you, perhaps I was trying to lift up my life a trifle. Heaven knows anyone’s life can stand a little of that.”

After all, we’re all talking creatures.